Posted By: Sara Cullinan, PhD, Deputy Editor, AJHG

Each month, the editors of The American Journal of Human Genetics interview an author of a recently published paper. This month we check in with Laïla El Khattabi and Alexander Hoischen to discuss their complementary papers Next-generation cytogenetics: Comprehensive assessment of 52 hematological malignancy genomes by optical genome mapping and Optical genome mapping enables constitutional chromosomal aberration detection

AJHG: What prompted you to start working on this project?

AH: I have been following the development of optical genome mapping (OGM) for years, but it was only two years ago that the technology seemed mature enough to run human clinical samples more routinely. At that time, we received the first data of four cytogenetically aberrant leukemia samples, and the data looked so convincing that we initiated both studies that were just published in AJHG. While our department invests heavily in sequencing-based technologies, we still continue to perform cytogenetic testing for several clinical diagnoses – and we saw an opportunity and use-case for OGM to innovate here for both germline and acquired cytogenetic aberrations.

Luckily, I met Laila at an OGM workshop at ESHG 2019 in Gothenburg. That’s when we agreed to join forces and start the French-Dutch consortium for the constitutional aberration study.

LEK: As a cytogeneticist, it is frustrating to watch the incredible revolution of genome analysis in terms of nucleotide variants and still have to perform the “old good” karyotype to search for chromosomal aberrations at a resolution of 5-10 Mb. The development of optical genome mapping using Bionano technology seemed to be the perfect simple alternative to our “out-dated” karyotyping. We naturally sought to test this technology for our patients bearing various chromosomal aberrations.

AJHG: What about this paper/project most excites you?

LEK: We feel that we are somehow contributing to a major breakthrough in the cytogenetics field, and this extremely exciting. It is remarkable that this new technology provides such amazing results while it is just starting to be applied as part of translational genomics. We are just at the beginning, and one can expect to see this technology improve more and more as the last gaps in human genome are filled out thanks to international efforts such as telomere-to-telomere consortium.

AH: Generally speaking, OGM is fascinating as it allows digitalized visual inspection of ultra-long DNA molecules or pieces of chromosomes. As such it may be considered “fiber-FISH on steroids” or simply “next generation cytogenetics”. The intuitive nature of the analysis, and visualization of (complex) chromosomal aberrations brought back my old love for cytogenetics (despite the still existing keen interest in sequencing in general).

In both studies we show very convincing concordance with standard-of-care approaches – and also very low false positive rates – and this is something that not only I am excited about, but more importantly, so are my colleagues who are diagnostic experts.

Both: We are also excited by the incredible team of scientists and diagnostic experts involved in these studies. We were blessed with true teamwork at play, and we hope this is only the start of more collaborations to follow.

AJHG: Thinking about the bigger picture, what implications do you see from this work for the larger human genetics community?

LEK: Although some limitations are still to be overcome, OGM will probably change the practice in clinical laboratories and allow new diagnoses in unsolved cases. In this regard, we are eager to move forward to the next step of translation to clinical use. With the increasing drop in its price, OGM could be easily used in conjunction with sequencing methods to provide a full picture of the genome for each patient referred for whole genome analysis.

AH: We hope we can encourage others to use OGM as an innovative cytogenetics method – and create an even broader user community. My optimistic self is convinced that OGM can replace almost all current cytogenetic assays – both in clinical research and diagnostics in the not too distant future.

This is also in line with several other studies that show that long-read technologies in general help us to assess regions of the genome that remained almost inaccessible with standard assays – and as such identify genetic variants that remained hidden. I am thrilled that long-read technologies have started to identify hidden (structural) variants that can explain so far unsolved (rare) diseases.

AJHG: What advice do you have for trainees/young scientists?

LEK: In a world where high throughput sequencing is the “go-to technology” in clinical genetics, our project evaluating a non-sequencing-based technique may seem unconventional. Indeed, it did not always receive the support that it deserved, in our opinion. Not that we absolutely wanted to take the opposite path, but we were conscious about the limits of current technologies and sought to complement them.

So, if I had any advice to provide it would be to pursue your own scientific convictions, after a thorough analysis of the situation, whether they are on trend or not.

AH: As a genomics technology fan I often show Sydney Brenner’s famous quote during teaching: ‘Progress in science depends on new techniques, new discoveries, and new ideas, probably in that order’. I think it is fundamental that young scientists realize that innovative methods can enable paradigm shifts. A broad human genetics view can educate the best choices of the right research or clinical questions that new approaches and applications can help answering.

- And for fun, tell us something about your life outside of the lab.

AH: I would consider myself a foodie. I love to travel and explore food and drinks in new cities and countries. I have a specific weakness for Italian cuisine, and I am very excited about my new 500⁰C pizza oven. I guess making your own dough and pizza sauces and then searching for the best ingredients is my compensation for the lack of experimental lab work. I also love to invite friends and colleagues to share this food passion. Hopefully the pandemic soon will wane, allowing a return to normalcy which will include extending invitations to our co-authors for a nice Italian pizza-and-wine event.

LEK: Between my clinical and research teams, and my lovely “private” team with my husband and our spirited 9 yo girl and 5 yo boy, I am quite busy and fulfilled. Besides that, what I love the most is hiking in the mountains of my adopted country, France, and helping people in need in particular in Morocco, my native country.

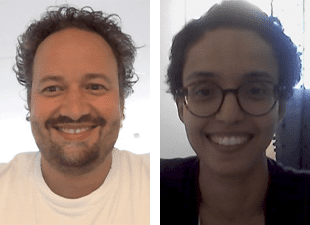

Dr Laïla El Khattabi is an associate professor at Cochin hospital and Université de Paris in France

Dr Alexander Hoischen is an Associate Professor at the Radboud University Medical Center, Nijmegen, The Netherlands, where he heads the ‘genomic technologies & immuno-genomics’ research group.