Posted by: Nalini Padmanabhan, MPH, Communications & Marketing Director, ASHG

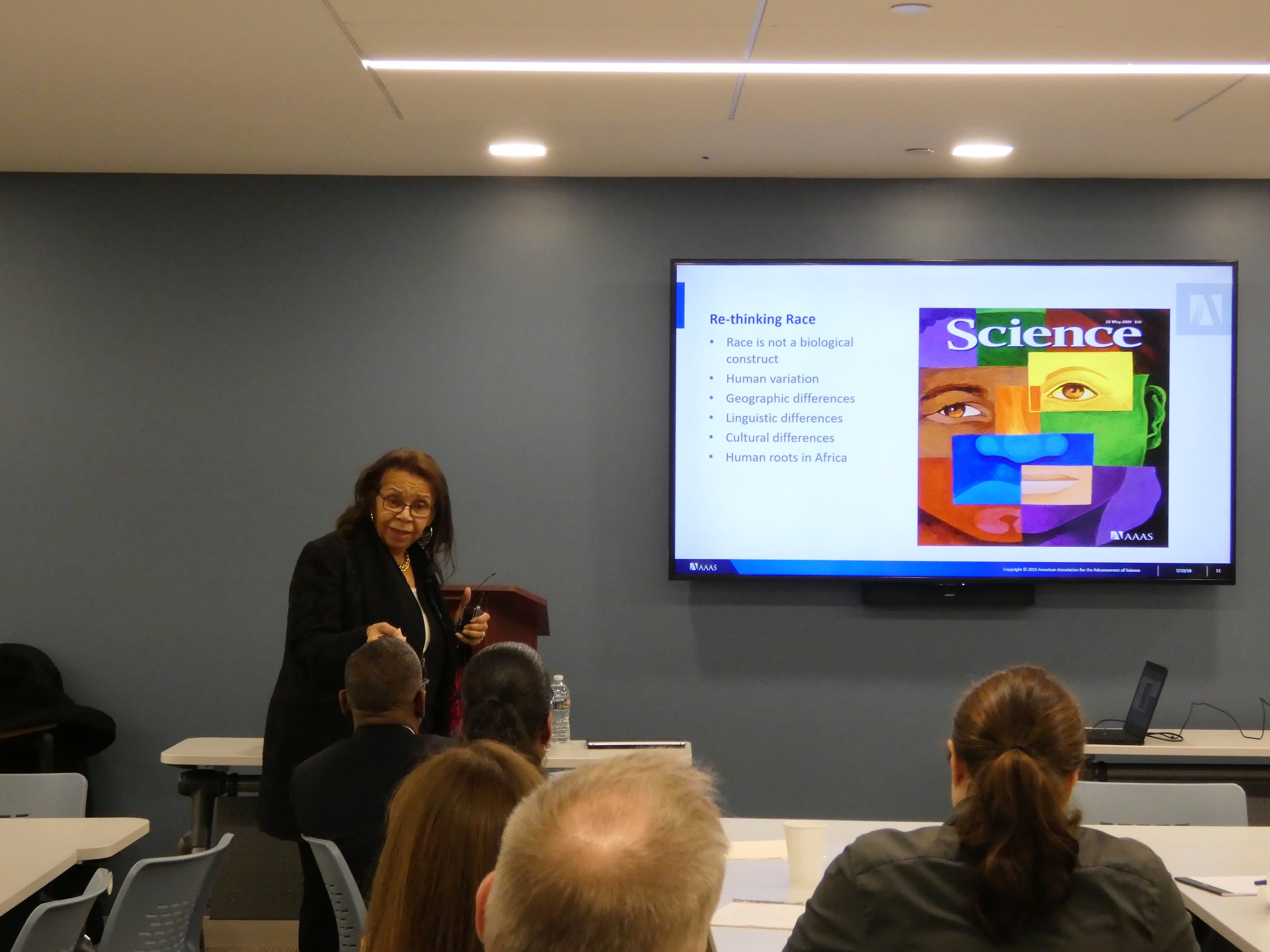

“Diversity is a scientific imperative,” said Vence Bonham, JD, in his introductory remarks to last week’s ASHG/Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology (FASEB) event, titled “What Difference Does Difference Make?”. The event featured keynote speaker Shirley M. Malcom, PhD, Head of Education and Human Resource Programs at the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS), who led an informative, interactive, and spirited discussion among nearly 70 staff at ASHG, FASEB, and several other FASEB member societies.

With strong board support, ASHG is already undertaking steps within our community to improve diversity and inclusion in science and exploring additional efforts. By sharing ideas and feedback with AAAS, FASEB, and other scientific societies, who face similar challenges and operate in similar environments, we are committed to building on successful strategies to raise our collective effectiveness.

Diversity in Genomics Research and Among Researchers

Dr. Bonham, Chief of the Health Disparities Unit at the National Human Genome Research Institute (NHGRI), set the stage by describing the importance of diversity in genomic research cohorts and in the genomics workforce. He cited several studies showing that the vast majority of genome-wide association studies (GWAS) and genetics-based disease studies in the public domain focused on populations of European ancestry. Though there has been some change in recent years, he noted, populations of African, Latin American, and Asian ancestry are still significantly underrepresented.

Diversity in the scientific workforce follows similar patterns, he explained: data show the relative representation of African American scientists declines at each step along the career path, from graduate school applicant all the way through department head.

Access to Scientific Opportunity, Power, and Science as a Human Right

“The challenge we have in this country is that we are both too polite and too impolite. There are things we don’t talk about because it makes us uncomfortable, and part of the challenge we have had is that we have not been honest in our discourse,” said Dr. Malcom, framing her discussion. “Inequalities related to sex, gender, race, and ethnicity are all part of the same issue, which is the distribution of power. We don’t talk about power much, but it drives much of what we see that we do not like,” she explained.

The 1948 Declaration of Human Rights, recognized explicitly by most countries, includes the right to the benefits of scientific progress. Furthermore, she said, scientific curiosity is part of being human, and unequal access to a scientific career reflects differences in power within the field and the educational system. For example, those who set the research agenda define which questions the field considers important, how findings are assessed, and how success is attained. These decisions tell an implicit story about what science is, who science belongs to, and who can do science.

Diversity Discussions Have Improved but Challenges Remain

Taking a historical perspective, Dr. Malcom traced how discussions of diversity have evolved since the 1960s and 1970s. Originally considering it solely as a legal issue related to civil rights, many started to improve inclusivity out of need – demographic shifts and a growth in research required more talent in the workforce. More recently, there is growing appreciation of the educational value of diversity as well as the innovation driven by a variety of perspectives and experiences.

“Today, women are the majority of students in higher education but not of the faculty,” she said. “There’s a mismatch between who is there and who teaches them, which affects the climate of the classroom. We need to create a new normal.”

Structural barriers and biases impede progress toward that new normal. These include difficulty in finding community and cultivating a sense of belonging, systematic undervaluing from faculty and peers, and a false assumption that difference equals deficiency.

That starts from admissions, she explained. “We have to get to a point where our programs recognize potential, not previously demonstrated performance, because not everyone has had the opportunity to actually be able to be successful in tests that we use to measure.”

Strategies and Current Efforts to Improve Diversity

Given these challenges, what can scientific societies do to improve diversity? Dr. Malcom offered several practical strategies. These include several activities that are increasingly front and center for ASHG. This year, we are beginning to track and emphasize greater diverse representation in our Annual Meeting program, and are working actively to promote more nominations and inclusion of diverse candidates for roles in society leadership and awards.

ASHG also will be exploring ways we can leverage and share with the field the learning, resources, and strategies of other leading groups, including SEA Change, an AAAS effort to support diversity and inclusion in STEM, especially in colleges and universities. It focuses on science departments and programs, helping them to identify unhealthy factors and instill best practices that create healthy cultures and foster diversity.

While the issue is complex, Dr. Malcom is confident the outlook is positive and sees more potential for progress in the scientific community. “We have evolved in the way we think about diversity in science. Now I think we are at a point where we can begin to talk about diversity, equity, and inclusion as central for excellence in research,” she said. “We all have our biases, but the question is: what do you do in spite of them and how do you overcome them?”