Written by Nascent Transcript writer Kathryn Vaillancourt

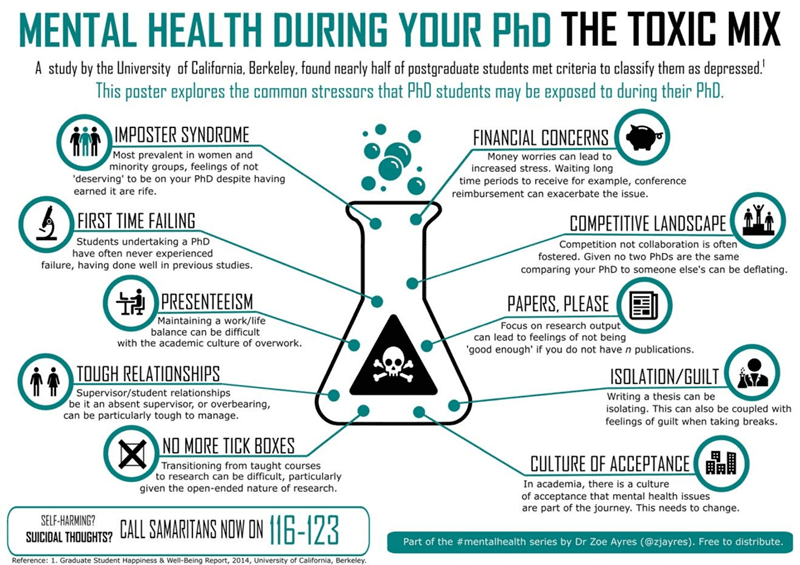

It was four years into grad school that I started to realise the extent of the negative impact that academia was having on my mental health. A report had just been published suggesting one in three PhD students was at risk of developing a common psychiatric disorder like major depression or anxiety. Although qualitative research is lacking in postdocs, the number of blog posts and stories from people echoing the same sentiment, from all levels of academia, is rising: we are struggling.

After years of struggling in silence, and a lot of introspection, I’ve realized that there are some specific aspects of academia that have negatively impacted my mental health. However, I have been working on strategies that help me weather the storm.

Uprooting your life and moving to an entirely new city or country is a common expectation in academia. For me, this meant leaving behind my entire support system of friends and family and left me feeling much more isolated than I expected (texts and video chats only go so far).

- As an introvert, I didn’t realize how badly I needed supportive people around me until they weren’t there, and although it took significant effort, reaching out and talking openly about my difficulties with mental health to my peers (both in-person and on social media) helped me re-build a small but strong network.

My life as an overachiever in undergrad left me unprepared for the ambiguous benchmarks of success and the many, many failures in research.

- I’ve been building my sense of self around academic achievements since grade school, so after years of what I perceived to be failure, surrounded by what looked like success in others, I decided I needed professional help. As a student, I started with counselling services offered by my school, and after multiple attempts at treatment, the best combination for me ended up being medication and Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT). Although I ended up with multiple psychiatric diagnoses, therapy can be beneficial long before a problem becomes an illness.

Traditional academic culture glorifies exhaustion. The idea that the only “good” grad student is the one that sleeps in the lab and never takes a holiday sets a dangerous and unsustainable standard.

- Having my whole life revolve around my work makes inevitable setbacks much more damaging to my ability to cope. Instead, I try to actively seek out extracurricular activities and hobbies that I genuinely enjoy, and allow time in my schedule to enjoy them. I’ve found that fostering other aspects of my personality beyond being a scientist has strengthened my confidence in the lab, too!

The issues surrounding the mental health crisis in academia are complex, and calls to action will take time to instill change in institutional policies and support systems. But in the meantime, we don’t have to struggle alone.

The Nascent Transcript invites you to anonymously share your story with other ASHG trainees in upcoming issues, so that we can learn from each other’s experiences and know that we aren’t alone in our struggles. Your story can involve issues at work, personal difficulties, or any problem that you’ve been struggling with, whether it’s resolved or ongoing.

For more information, including warning signs of mental health decline and resources for help: https://www.gograd.org/resources/grad-student-mental-health/

For an online support network of graduate students: www.phdbalance.org